The 101 Dishes That Changed America

How did we find the 101 dishes that broke the restaurant mold and forever changed the flavor of America? We looked for dishes that have been endlessly adopted or outright copycatted on other menus, kicked off a lasting trend, or became staples that still define the way we eat today in 2018.

That meant a simple sandwich creation that became a nationwide staple so beloved anyone can tell you the ingredients. It meant a landmark dish from a paradigm-shifting chef. It meant a reimagining of a classic that cast a once-famous dish in an entirely new light, or an overseas sensation that made its mark from thousands of miles away. While the backstories and particulars may vary, these 101 restaurant dishes all left an enduring imprint on America, and life quite simply wouldn’t taste the same without them.

1910s | 1920s | 1930s | 1940s | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s

1. Hot Dog

Year: 1916

Restaurant: Nathan's Famous Hot Dogs

Coney Island, New York

How it happened: The story as to how Nathan's Famous officially came to fruition has many versions, but the founder's official tale (as reported by The Daily Sentinel in 1974) goes as such: German immigrant Nathan Handwerker was working as a low-level employee at Feltman's German Gardens on Coney Island, when two of the restaurant's singing waiters complained about the price of Feltman's 10-cent hot dogs, and challenged the young bread slicer to create a cheaper, better coney. And that's what he did. Handwerker undercut his old employer's prices by a full 5 cents, and used his young bride (and business partner) Ida's secret spicing recipe to create a better tasting dog. The uptick in quality and downtick in pricing made all the difference. Feltman's has become a historic blip on the wiener-radar, while Nathan's has become a national institution, with more than 14,000 locations all over world -- and one incredibly famous annual hot dog eating contest right where it all started in Coney Island, 102 years ago.

Why it's important: Nathan and Ida Handwerker certainly didn't invent the hot dog. Nor did they even lay the framework for the coney dog as we know it today. They took something that was already popular, made it better and cheaper than the competition, and created a scalable business model in the process. "I think our role in how popular hot dogs are today is substantial. We have been satisfying hot dog lovers for generations, and we are the No. 1 selling premium hot dog for a reason," said Phil McCann, Senior Director of Marketing for Nathan’s Famous. Nathan's set the mold for every American restaurant that would follow in its dirty-water wake: You don't necessarily have to be "the first" to succeed. But it certainly helps to be the best… and it definitely helps to be the cheapest. -- WF

Photo: Cole Saladino/Thrillist

2. Coney Island Hot Dog

Year: 1917

Restaurant: American Coney Island

Detroit, Michigan

How it happened: Technically, the coney dog -- which has absolutely nothing to do with New York, thank you very much -- first appeared in Jackson, Michigan. But it was in Detroit circa 1917 that American Coney Island first started dropping its wet, immaculately spiced chili on dogs, paving the way for legions of Greek immigrants to follow suit, among them the rival coney Lafayette right next door, founded by a Keros family member and the topic of an oft-misunderstood and exaggerated "feud" of Detroit food lore. But it was American that started it all, transforming that dripping, mustard- and onion-covered masterpiece on a bun into the unofficial food of lower Michigan.

Why it’s important: “Detroit is industrial, automotive; this is a working-class town, a working-class state. It was affordable back then and now, is quick and comforting and filling: That's how it became such an important part of the city and state, and why you can't find coneys (anywhere else)” said Grace Keros, third-generation owner (along with brother Chris Sotiropoulos) of Michigan's oldest family-run restaurants. Because of American, the coney became a paragon of the Greek-diner experience, one that still thrives throughout the Midwest even as the institutions close across the rest of the countries. Such is the power of the perfect hot dog. -- AK

Photo: Jeff Waraniak / Thrillist

3. The French Dip

Year: 1917

Restaurant: Philippe the Original

Los Angeles, California

How it happened: The details of the origin of the French dip are hazy, and get hazier depending on who’s telling it, with both Philippe’s and Cole’s claiming to have invented it in a nearly century-long rivalry. If Philippe is to be believed, the dish itself came about by accident: “It originated in 1917,” fourth-generation owner Mark Massengill told TV show Cheap Eats. “Philippe Mathieu was carving a roast beef sandwich for a fireman and the bread accidentally dropped into the roasting pan... ” Other variations say it was a cop named French, and it was gravy from roast pork. No matter. Philippe’s makes 2,000 of them a day, but the dish’s influence swept through the sandwich world, helping it embrace sogginess, whether it’s via dipping a hoagie in a side of au jus or dunking the whole damn thing in a bucket of gravy, dry cleaning be damned.

Why it’s important: The French dip -- arguably LA’s most iconic food despite most people thinking it has more in common with Paris than Hollywood -- has become one of America’s favorite sandwiches, emulated in nearly every diner in the US. It's so pervasive that even Arby’s has a version. Regardless of who truly created the first one, Philippe’s made it an icon. -- AK

Photo: Dustin Downing/Thrillist

4. The Reuben

Year: c. 1920

Restaurant: The Blackstone Hotel

Omaha, Nebraska

How it happened: The Reuben’s origins have endured more shade than almost any other dish. When writer Elizabeth Weil penned a back-page New York Times piece titled “My Grandfather Invented the Reuben Sandwich. Right?” she received enough to warrant a thinkpiece in Saveur four years later. As Weil whimsically (and sometimes doubtingly) tells it, and many believe, the sandwich was invented when her hotelier great-grandfather was playing poker after hours in the Blackstone Hotel. A customer named Reuben Kulakofsky asked for a sandwich with corned beef and sauerkraut. “In the kitchen, my grandfather, who spent the previous year perfecting his sauces and ice-carving skills, drained the sauerkraut and mixed it with Thousand Island dressing," Weil wrote. "The sandwich was a hit.” That’s a huge understatement.

Why it's important: Many poke holes in this family story. Others lay claim to it. But in addition to representing a wonderful modern tall tale that sprang to life and still riles debate, the Reuben is, in and of itself, a wonderfully Midwestern affair. It's a non-kosher mashup of Jewish deli mainstays that has become a go-to at the delis that inspired it, plus every other diner, sandwich shop, and brewery in the country. Plus, if you do believe Weil’s story, you can still get a taste of the original, though not at the Blackstone itself: Across the street, beer bar Crescent Moon still uses the old Blackstone recipe from an old typewritten transcript. And they still insist, as tradition demands, that it’s the original. -- AK

Photo: Cole Saladino; Styling: Ali Nardi

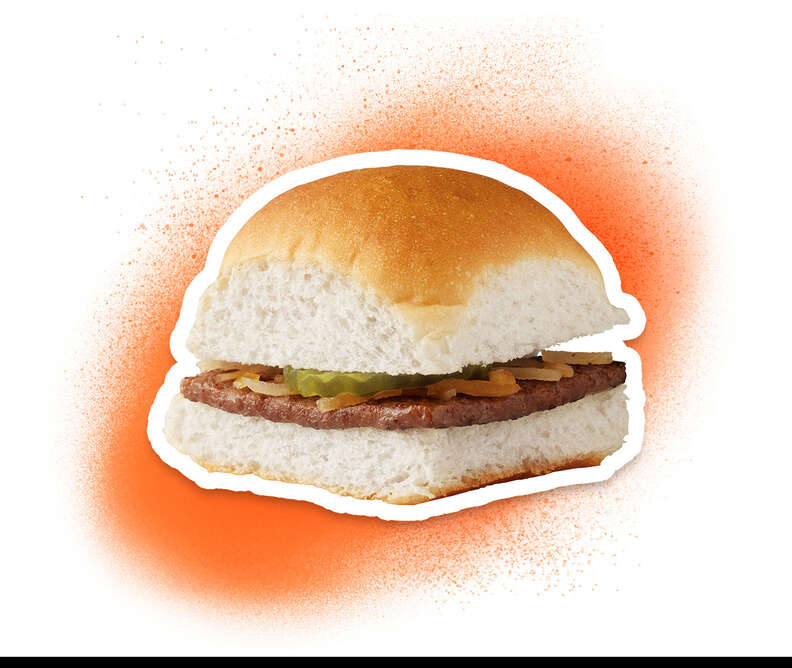

5. The Original Slider

Year: 1921

Restaurant: White Castle

Wichita, Kansas

How it happened: It's hard to fathom now, but America's biggest burger-related problem at the dawn of the roaring '20s was an aversion to beef, rather than an addiction to it. "At the time, self-respecting moms would not feed their children hamburgers," said White Castle vice president Jamie Richardson. "Upton Sinclair had written The Jungle, and it wasn't a flattering picture of the meatpacking industry or beef in general." Founder Billy Ingram used $700 to open his first White Castle in Wichita, Kansas with a plan to win over customers not only with tiny, tasty, square-shaped burgers that cost a nickel, but also with gleaming white storefronts and crisp, clean uniforms that he hoped would inspire public confidence. They did, and decades before anyone had heard the name McDonald's, America had its first burger chain success story.

Why it's important: Beyond marking the beginnings of America's love affair with the fast-food burger, White Castle provided a model for every fast-food chain that would eventually populate the country's highway exits, suburban strip malls, and, well, just about everywhere else. Furthermore, "sliders," a name coined for how easily the tiny burgers slide down one's gullet, have become an increasingly popular appetizer staple in recent years. -- ML

Photo: Courtesy of White Castle

6. Caesar Salad

Year: c. 1924

Restaurant: Caesar's

Tijuana, Mexico

How it happened: In the 1920s, the Mexican border city of Tijuana was a refuge for well-heeled Californians escaping the Prohibition doldrums. The Hollywood set flocked to Caesar’s, a restaurant run by the Italian-American restaurateur, Caesar Cardini, who, in addition to his booze, was known for his namesake salad. Word has it that Cardini improvised the tableside preparation of romaine with egg yolk, anchovy paste, mustard, minced garlic, anchovy, olive oil, lemon juice, and Parmesan cheese to feed diners during a holiday meal when supplies were running low. The salad became famous, but over the years, Caesar’s itself declined. About a month after the restaurant finally shut down in 2010, chef and Tijuana champion Javier Plascencia took over the space, and restored Caesar’s to its original dignity, tableside prep included. “We have a waiter who has been doing this for many years,” said Plascencia. “You can see it in his face: He is very proud, and you can taste it in the salad.”

Why it’s important: The unbeatable mix of cheese, garlic, anchovies, egg, mustard, crunchy romaine, and croutons have made this the most famous salad in the world. Plus, Caesar is enduring and adaptable -- from bottled Caesar dressing to grilled chicken Caesar to the kale Caesar of the aughts, its popularity is indisputable. No matter where you travel in US, you are bound to find a Caesar salad on the menu. -- Gabriella Gershenson

7. Cobb Salad

Year: 1926

Restaurant: The Brown Derby

Los Angeles, California

How it happened: The oft-debated story goes: In 1926 Bob Cobb, owner of the famed Brown Derby restaurant, felt peckish after closing time, so he threw together leftovers he came across in the kitchen -- iceberg lettuce, frisée, romaine, watercress, tomato, chicken, avocado, bacon, hard-boiled egg, and blue cheese -- and tossed them with French dressing. He enjoyed it so much that he put it on the menu. It subsequently became a favorite of local celebrities, and a salad sensation was born. The dish was “one of the most sought-after salads since the discovery of lettuce,” Gail Monaghan wrote in The Wall Street Journal. “This main-course salad was a culinary breakthrough that continues to hit the spot almost a century after its invention.”

Why it’s important: Not since the Caesar has a salad been so famous. The Cobb introduced the concept of a main-course salad (very California), a hearty, protein-laden assemblage in a giant bowl. Its Hollywood-esque origin story has been so legendarily disputed that it is even winked at on an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm. Though the original Brown Derby closed in 1985, the Cobb salad remains a staple of menus across the country, including at a recreation of the Brown Derby at Disney's Hollywood Studios in Orlando, Florida. -- K. Squires

8. Lobster Roll

Year: c. 1929

Restaurant: Perry's

Milford, Connecticut

How it happened: Though Maine is typically regarded as the nation’s lobster roll capital, the quintessential summer dish was most likely birthed about 250 miles south in the small coastal town of Milford, Connecticut. Between 1927 and 1977, a restaurant there named Perry’s served simple New England seafood fare. According to the Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, author John Mariani wrote that this no-frills restaurant may have invented the lobster roll. “Owner Harry Perry concocted it for a regular customer named Ted Hales sometime in the 1920s,” Mariani wrote. “Furthermore, Perry's was said to have a sign from 1927 to 1977 reading, ‘Home of the Famous Lobster Roll.’” Other customers began to clamor for the warm, butter-drenched lobster sandwich, and Perry’s began serving them regularly on a special proprietary roll created by now-shuttered local bakery French’s.

Why it’s important: If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then Perry’s can rest easily on its laurels: The lobster roll proliferated all over New England, even spawning regional varieties. The Connecticut version invented by Perry’s is simple: warm lobster meat drizzled with melted butter and piled into a toasted bun. In Maine, rolls or buns are filled with what is essentially lobster salad, cold meat folded with mayo and some aromatics such as celery or tarragon. While the Maine style typically prevails, only Connecticut can lay claim to the original version. -- LR

9. Macarons

Year: 1930

Restaurant: Ladurée

Paris, France

How it happened: In 1862, Louis Ernest Ladurée opened a petite bakery on Rue Royale in Paris. Less than a decade later, it blossomed into a cherub-adorned pastry shop, and soon a salon de thé, where ladies banned from the city’s café culture could cavort freely. That same revolutionary spirit was on display in 1930, when Ladurée’s cousin Pierre Desfontaines transformed the traditional macaron cookie -- a simple recipe of almond, sugar, and egg white purportedly brought to France from Italy by Catherine de' Medici -- by piping the top with ganache and sealing it with another macaron. This ethereal sweet, equal parts crunchy and creamy, became the star of Ladurée. When the family of Elisabeth Holder Raberin, co-president of Ladurée US, took over the company in 1993, amping up the macaron was a priority. Instead of just classics like vanilla and chocolate, there was now salted caramel, pastel-hued rose, and seasonal specialties. “It's the supermodel of food,” said Holder Raberin.

Why it’s important: Under the leadership of the Holder family, Ladurée has expanded to some 150 locations around the globe. Its New York debut in 2011 provided a daintier, more cosmopolitan alternative to the city’s previous baked obsession, the cupcake. Significant moments in both Gossip Girl and Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette, not to mention appearances in magazines like Vogue, further helped cement the macaron's role in pop culture, and as the world’s most glamorous cookie. -- AA

Photo: Cole Saladino/Thrillist

10. The Cheesesteak

Year: 1930

Restaurant: Pat's King of Steaks

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

How it happened: Like fellow Philadelphia great Rocky Balboa, the cheesesteak’s rise came as something of a surprise. Founders Pat and Harry Olivieri were operating a hot dog stand, and decided to switch things up, throwing chopped steak, cheese, and grilled onions on a bun. According to legend, a cabbie saw what they were eating and ordered it. Then he told... well, pretty much everyone. The Oliveris switched their focus to grilling up thin-sliced rib-eye, and half of Philadelphia followed suit, giving birth to intense intra-city rivalries and a sandwich style that has long been a national mainstay, even if die-hards insist that no quality version exists outside of Philly.

Why it's important: The cheesesteak transitioned from regional specialty to one of America's favorite sandwiches over the decades, and for good reason. "You can go anywhere in Europe or the US and find a Philly cheesesteak. Say 'yeah, give me a Philly’ and they know what that is," said owner Frank Olivieri, Jr., Pat's great-nephew, who says he, like so many Philadelphians, started eating cheesesteaks in the womb. “It’s just an amazing sandwich. To me, it falls in the same category of the perfect pastrami on rye, the perfect corned beef sandwich, or the perfect slice of New York pizza.” -- AK

Photo: Courtesy of Pat's King of Steaks

11. The Pitts-burger

Year: 1933

Restaurant: Primanti Bros.

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

How it happened: Primanti's was originally a standard sandwich shack in Pittsburgh's Strip District -- a hub for dock workers and other blue-collar city dwellers. According to Primanti's spokesperson Ryan Wilkinson, one fateful day, a nearby produce worker showed up with a sack of potatoes (naturally) wanting to test whether or not they were frozen. "They let him chop them up and stick them on the grill," he said. "Someone saw the freshly grilled potato slices and decided they wanted them on their sandwich." Thus, the fully loaded Pitts-burger sandwich (complete with coleslaw and a thick slice of beef on fluffy white bread) was born. It might even be Pittsburgh's most enduring and celebrated cultural icon -- after Mr. Rogers, of course.

Why it's important: "Even though we didn't mean to at the time, we really reinvented what a sandwich could be," Wilkinson said. "It wasn't just about mustard and bologna on a roll anymore. This is a meal." Though the simple addition of fries to a standard sandwich might seem like a basic move in today's "loaded sandwich" arms race, the notion of stepping outside standard sandwich ingredients was relatively unheard of at the time. So the next time you're pumped to encounter mozzarella sticks, onion rings, or some other "I didn't know they could do that!" ingredient on your sandwich, take a second to pay homage to that sack of frozen potatoes that ended up changing American food forever on a chilly western Pennsylvania day. -- WF

Photo: Courtesy of Primanti Bros

12. Toll House Cookies

Year: 1936

Restaurant: Toll House Inn

Whitman, Massachusetts

How it happened: The mainstream narrative speculates that the chocolate chip cookie was a chance discovery, positing that Ruth Graves Wakefield accidentally knocked over some chocolate into a stand mixer containing dough for her Butterscotch Drop Do cookies. There are other ways the legend goes, but any story that makes the chocolate chip cookie out as an accident is wrong. A prodigious chef and an even better baker, Wakefield was known to keep a tight ship, and she incessantly perfected her recipes; never would a mistake have made its way to her customers' plates. "We had been serving a thin butterscotch nut cookie with ice cream. Everybody seemed to love it, but I was trying to give them something different," Wakefield told the Boston Herald-American in 1974 recalling the cookie's invention. Her chance on "something different" was a massive hit, and she sold her Toll House cookie recipe to Nestle for $1, a sum she never received.

Why it's important: The Toll House Inn has since been destroyed by a fire and replaced with a Wendy's, but Wakefield's chocolate chip cookies have been so deeply imbued into the American dessert canon that it's easy to forget that they needed inventing at all. It was one of the first times that a recipe was commodified (hardly anything more American than capitalism!). Pulling apart cold logs of store-bought Toll House cookie dough is often the first-ever interaction with baking, or cooking in general. Quite simply, chocolate chip cookies themselves rival apple pies for chief American dessert. -- LB

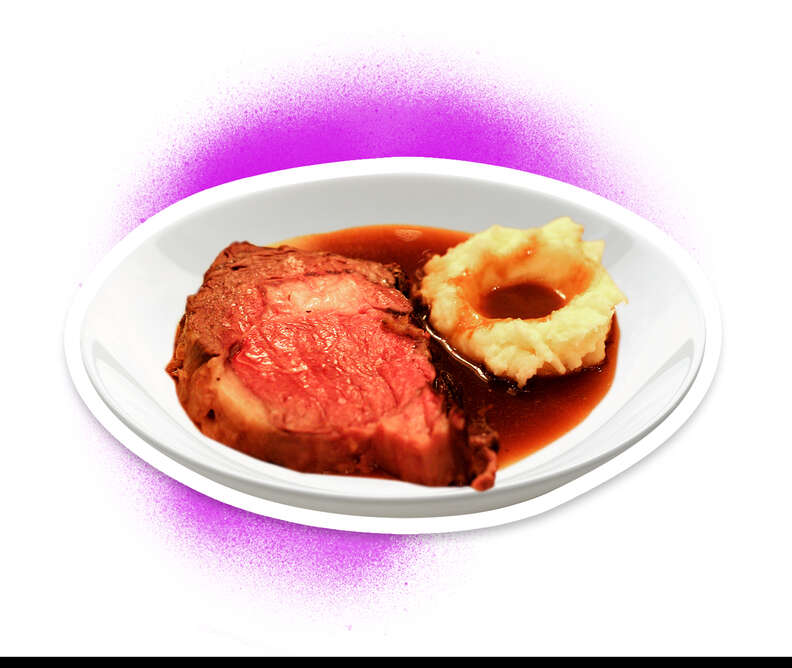

13. Prime Rib

Year: 1938

Restaurant: Lawry's

Los Angeles, California

How it happened: Lawrence Frank and Walter Van de Kamp shaped their Beverly Hills restaurant in the image something between a Midwestern Sunday night family dinner and Simpson's in the Strand, one of London's oldest traditional restaurants, known for rolling silver carts of roast meat through the dining room to serve tableside. The brothers-in-law -- with a budding LA restaurant empire having already opened the Van de Kamp Bakery and Tam O'Shanter Inn -- saw an opening to provide quality prime rib meals in a fine dining setting. To assure a constant flow of customers, they designed a flashier experience, where slabs of buttery tender prime rib were carved tableside on carts of Frank's design: an art deco shape cut in stainless steel, 4 feet long, and more than 500 (!) pounds, fully loaded with meat and sides. "My great-grandfather [Lawrence Frank] used to call prime rib the greatest meal in America, and I still think it is," said Ryan Wilson, executive chef at Lawry's. Frank wasn't wrong: Lawry's was an instant hit.

Why it's important: Prime rib was literally the only entree on Lawry's menu until 1993. Otherwise, the restaurant has hardly changed over the past 80 years, remaining one of the most classic LA restaurants on Restaurant Row, giving diners a moment to revel in the theatrical doting consistency of old-school tableside service, and outliving its failed imitators. "We still carve the prime rib tableside -- a tradition for us, but something that we’re now seeing crop up around the country in new and exciting ways," Wilson said. -- LB

14. Fried Chicken

Year: 1940

Restaurant: Kentucky Fried Chicken

North Corbin, Kentucky

How it happened: These days, we think of Harland Sanders as a lovable, shape-shifting Kentucky colonel with the body of Billy Zane and the voice of Reba McEntire. But back in the day, Sanders was a magnificent huckster, traveling the land with a dream: to give every city a solid bucket of fried chicken that would taste the same anywhere, thanks to the secret recipe and a unique pressure-frying system that ensured that extra-crispy bird, punched up by the signature 11 herbs and spices. The first franchise was established in 1952. Today, KFC operates more than 4.200 stores worldwide.

Why it’s important: "Part of how he grew the company was by developing solid franchise partnerships across the US, some of which are still in place today," said Kevin Hochman, US President of KFC. "Ensuring they make our hand-prepared world-famous Kentucky Fried Chicken consistently in our kitchens across the US is no easy feat." But the feat proved worth the effort, with Sanders becoming the poster-colonel for the American fast-food franchise model, and his iconic, faithfully recreated chicken recipe becoming a staple at picnics, family reunions, and impossibly busy weeknights worldwide. -- AK

Photo: Cole Saladino/Thrillist

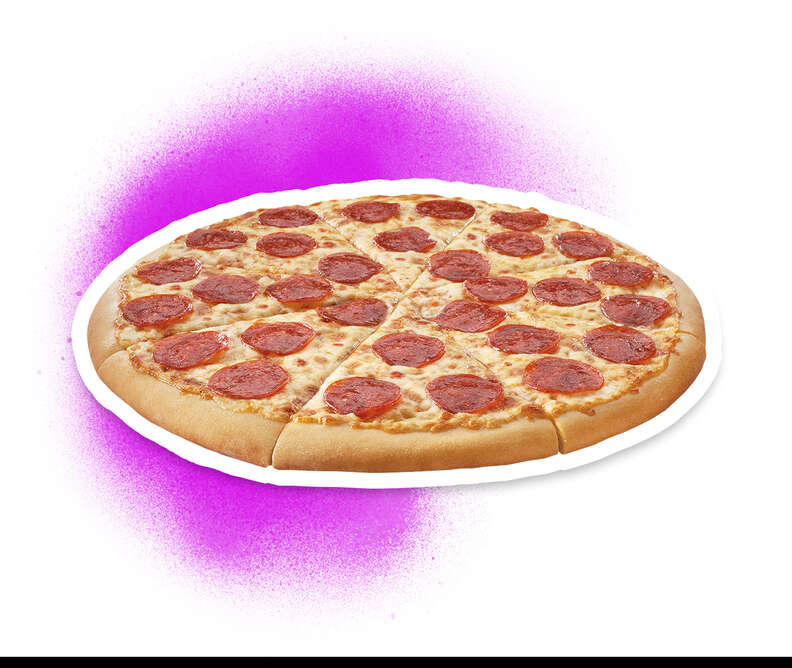

15. Deep-Dish Pizza

Restaurant: Pizzeria Uno

Year: 1943

Chicago, Illinois

How it happened: Ike Sewell and Ric Riccardo had but a humble vision when they decided to go into the restaurant business: create something that would satiate the voracious hunger of Midwesterners. They created a monster. “The vision was to create a meal, not just a pizza with a little bit of toppings and some cheese,” said Skip Weldon, chief marketing officer for Uno Restaurants. Pizzeria Uno’s creation is still enough to give eaters pause: buttery, thick crust; sauce up top, hiding enough cheese and toppings to feed an entire section at Wrigley. Hundreds of Chicago restaurants now serve a variation on Sewell and Riccardo’s creation, which is now as associated with the city as hot dogs and the blues.

Why it's important: We’ll leave the debate about whether it’s really pizza to angry New Yorkers: Deep-dish pizza is a cultural phenomenon, and its originator is the global ambassador, having begun franchising in 1970s and spreading the love of gut-busting Chicago pizza across the globe (and into the mail system, as they recently started shipping pies). Even Chicago’s other institutions-turned-chains can be traced back to Uno’s. “(It) spawned a lot of different restaurants trying their hands at deep-dish pizza,” said Weldon. “In fact, Lou Malnati’s father Rudy Malnati worked at Pizzeria Uno. Giordano's, Gino’s East, all of those restaurants had connections back to the original Pizzeria Uno. It’s kind of the deep-dish family tree.” -- AK

Photo: Courtesy of Uno Pizzeria & Grill

16. Nachos

Year: 1943

Restaurant: El Moderno

Piedras Negras, Mexico

How it happened: During World War II, the small Texas border town of Eagle Pass was home to a US Air Force training base, and servicemen’s wives would often cross the border to the Mexican town of Piedras Negras looking for good food (and a shot or two of tequila). According to Robb Walsh in The Tex-Mex Cookbook, it was here that nachos were born. Lore has it that when four women entered El Moderno restaurant for a round of drinks, and they asked for a snack, but their waiter, Ignacio Anaya, couldn’t find the cook. So “Nacho” -- a common nickname for those named Ignacio -- went into the kitchen, sliced tortillas into quarters, piled on cheese and sliced jalapeños, and stuck the plate under the broiler. “The women loved the cheesy crisps and wanted to know what they were called so they could order them again,” Walsh wrote. “‘Just call them Nacho’s Especial,’” Anaya told them. Eventually shortened to “nachos,” the dish became El Moderno’s most popular appetizer.

Why it’s important: Legions of happy-hour revelers across the country can attest to the importance of the nacho: It’s the ideal dish for soaking up one too many drinks. Practically any bar with a kitchen serves the mess of tortilla chips, with toppings that range from convenience store foods (Cheez Whiz, Velveeta) to the upscale (Brie, duck confit). -- LR

Photo: Cole Saladino; Styling: Ali Nardi

17. Hot Chicken

Year: 1945

Restaurant: Prince's

Nashville, Tennessee

How it happened: Turns out, revenge is a dish best served hot. In the 1930s, a woman in Nashville found out that her lover, Thorton Prince, had been spending his time with multiple women around town. Fed up with his cheating ways, she decided to get revenge by sabotaging his favorite dish: fried chicken. She dumped a ton of cayenne pepper and spices onto a batch of freshly fried chicken that she’d made for him one Sunday morning and waited for him to take a bite and double over in pain. To her surprise, not only did he eat the entire batch of chicken, he loved it and asked for seconds. Thorton even saved some of the spicy chicken and brought it to his brothers who loved it, too. In 1945, Thorton and his brothers opened the first location of Prince’s Hot Chicken in Nashville, Tennessee with a recipe that they’ve perfected and worked on for years.

Why it's important: Hot chicken stayed a local Nashville specialty until 2007, when the city of Nashville hosted its first Music City Hot Chicken Festival, introducing non-Nashvillians to the dish. Since that festival, the gospel of hot chicken has spread across the country and has even been adopted by fast-food chains. KFC introduced their Nashville Hot Chicken meal in 2015, complete with bread and butter pickles. In the era where food television can propel local, regional dishes to a national audience, hot chicken was the perfect subject for chef-y shows like Food Paradise and Mind of a Chef. Andre Prince Jeffries, Prince Thorton's great-niece who runs the restaurant today, said she’s not phased by the competitors. “My customers, they try all these different places that are popping up,” she said. “They come right back here.” -- Korsha Wilson

Photo: Courtesy of Prince's

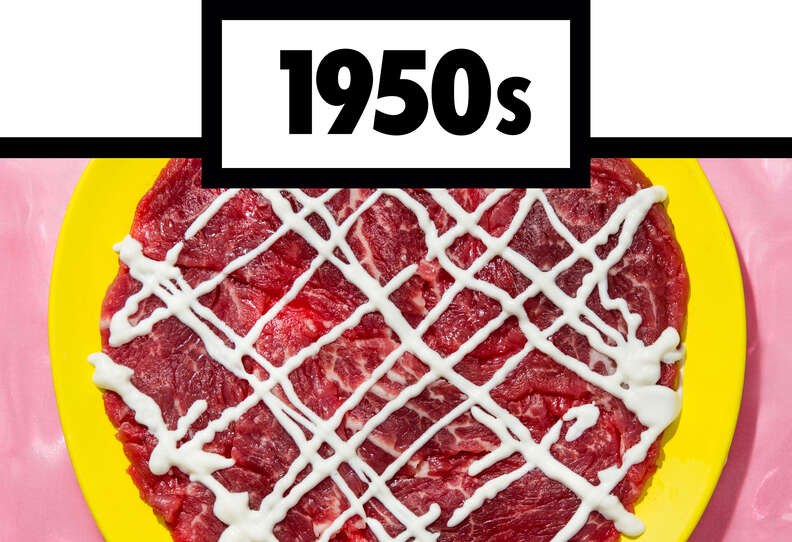

18. Carpaccio

Year: 1950

Restaurant: Harry's Bar

Venice, Italy

How it happened: Many a visitor to Venice have made the obligatory pilgrimage to Harry's Bar to sip a Bellini and soak in the same ambiance that so enchanted Ernest Hemingway, Charlie Chaplin, and (insert your favorite historical figure because they probably drank here). Another former patron you should celebrate: contessa Amalia Nani Mocenigo, who one day came at lunch and tearfully informed owner Giuseppe Cipriani that she could no longer eat cooked meat. According to Cipriani's son Arrigo's account in the book Harry's Bar, his father came back within 15 minutes with a plate of tissue-thin raw filet mignon drizzled with mayonnaise-mustard sauce, inspired by the vibrant red-and-white paintings of the eponymous artist.

Why it's important: While the components and presentations have come to vary widely over the years, carpaccio has come to represent an entire category of thinly sliced, artfully plated edible arrangements, from tuna to duck to all sorts of plant-based preparations. It's become so ubiquitous that many diners are unaware of its highly specific and fairly recent origins, as the younger Cipriani wryly noted: "If my father had been a bit more egotistical, or as we would say today 'PR oriented,' the famous dish could just as fairly have been called Cipriani." -- ML

Photo: Cole Saladino; Styling: Perry Santanachote

19. Chimichanga

Year: c. 1950

Restaurant: El Charro

Tucson, Arizona

How it happened: This deep-fried burrito with Southwestern roots is just one of many famous dishes that fall into the “oops, I invented a classic” category. According to Ray Flores, fourth-generation owner of El Charro, the chimichanga came to be in the early 1950s, while his great-great-aunt Tía Monica Flin, founder of the Tucson restaurant, was looking after her nieces at a slumber party. As she prepared a mountain of beef burritos for the girls, one slipped off the stack and into a pot of bubbling oil. “Flin was angry but refrained from muttering the Mexican expletive 'chingada' in front of the kids,” journalist Margaret Regan wrote in Edible Baja Arizona. “Instead she blurted out a variant: chimichanga.”

Why it’s important: After Flin’s test audience went gaga over the chimichanga, she added it to El Charro’s menu, where it has remained ever since. Established in 1922, El Charro is the country’s oldest Mexican restaurant continually operated by the same family, and one of the most influential. The chimichanga spread far and wide, to chains like Chili’s and TGI Fridays, helping solidify Tex-Mex as one of America’s beloved cuisines. -- LR

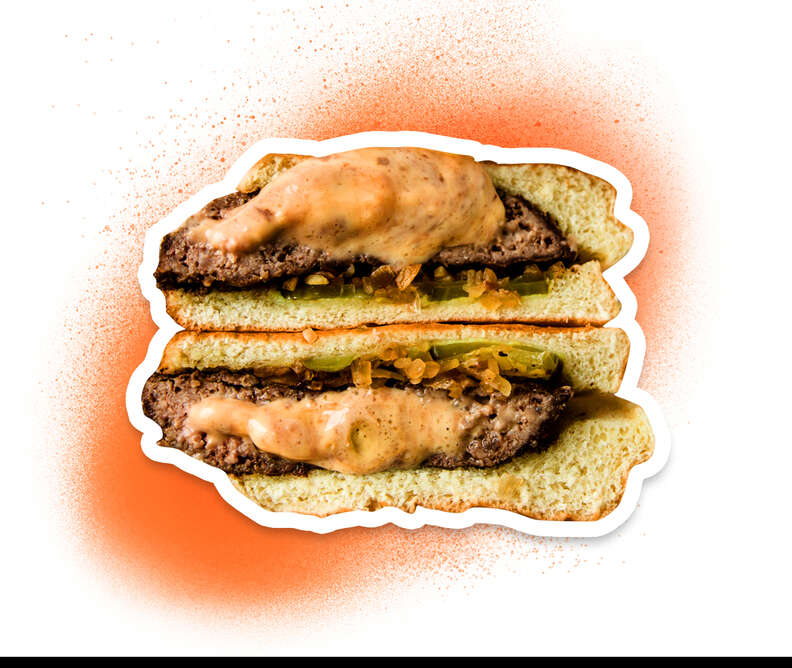

20. The Jucy Lucy

Year: c. 1950

Restaurant: Matt’s Bar

Minneapolis, Minnesota

How it happened: A gloriously simple bar burger stuffed with molten cheese, the humble Jucy Lucy has been providing accidental burns to the mouth for decades: "You boys know you need to wait a minute or two,” a Matt's Bar waitress told our burger critic on one visit. “Or you’ll get burned.” Two Cedar Avenue bars in Minneapolis claim to have invented the thing -- 5-8 Club and Matt’s -- though it can now be found at pretty much any Minnesota bar that operates a grill. Given the bars’ close proximities to one another, it’s entirely plausible that the same weirdo customer who originally ordered two patties with cheese in the middle just walked up and down Cedar Avenue ordering the same thing, and both Matt's and 5-8 put it on the menu. But Matt’s has stuck to its story much more consistently, and made the burger an icon thanks both to its delicious execution and its steadfast misspelling of “juicy.”

Why it’s important: Long before Doritos Locos Tacos and mac & cheese-stuffed Cheetos, stunt food was a much simpler endeavor. The Jucy Lucy is a precursor to that, but it’s also an important milestone in the evolution of hamburgers themselves, leading the charge for industrious chefs (and more than a few infomercial entrepreneurs) to begin stuffing their burgers. -- AK

Photo: Ashley Sullivan/Thrillist

21. Bananas Foster

Year: 1951

Restaurant: Brennan's

New Orleans, Louisiana

How it happened: Throughout the 20th century, New Orleans was the country’s largest importer of bananas. In 1951, the original location of the storied NOLA restaurant Brennan’s honored local businessman and Brennan family friend Richard Foster with a dinner. At the time, John Brennan, father of current owner Ralph, ran a small produce company and faced a surplus of the fruit; so for the dinner, Ralph’s aunt, Ella, and Brennan’s chef, Paul Blangé, came up with a sweet way to use up the overstock. “My aunt Ella’s mom used to bruleé bananas for the kids at home, so that’s where the idea came from,” Ralph Brennan recalled. Blangé elevated Ella’s idea, serving a dish of bananas, butter, brown sugar, and cinnamon flambéed with banana liqueur, and served over vanilla ice cream. “It was somewhat spontaneous, and the rest is history: It’s become legendary.”

Why it’s important: Today, New Orleans is recognized as a world-class dining destination, but that wasn’t always the case. Acceptance of, and acclaim for, its rustic Cajun and Creole cuisines built slowly over the decades. Brennan’s bananas Foster helped establish New Orleans as a serious food town. The dessert has also become a popular flavor in its own right -- see Bananas Foster Baskin-Robbins ice cream, Bananas Foster Keurig cups, and the Cheesecake Factory’s Bananas Foster cheesecake. -- Lauren Rothman

Photo: C. Ross / Thrillist

22. Concrete

Year: 1959

Restaurant: Ted Drewes

St. Louis, Missouri

How it happened: Ted Drewes is not like all other summertime ice cream shops in the Midwest. For one, it sells custard. For two, only Ted Drewes can correctly assert that they invented the concrete. Thirty years after Ted Sr. opened the first frozen custard stand in 1929, the 1950s version of a teenage troll would roll up to Ted Jr. working in the summer asking for his shake to be mixed as thick as possible. Ted Jr. eventually got sick of this request, and as the story goes, he tossed in the toppings with the custard, but omitted milk. The result was a shake so dense, Ted Jr. served it to the teen upside down. "There, is that thick enough?" "That’s just like concrete," replied the neighborhood teen. Ever since, a Ted Drewes concrete has ranked in the echelons of foods synonymous with St. Louis, along with toasted ravioli, gooey butter cake, and, unfortunately, Provel on pizza.

Why it's important: Do you enjoy an occasional DQ Blizzard, McDonald's McFlurry, Shake Shack concrete, Culver's frozen custard, or any other stiff, topping-studded cold treats you eat with a spoon? Then you owe a debt of gratitude to Ted Drewes. "It is as American as a Bobby Thompson home run, an Ed Macauley hook shot or a Ted Drewes 'concrete' on a hot summer night," reads a Post-Dispatch analogy that definitely held up better 50 years ago than it does now. -- LB

23. White Clam Pie

Year: c. 1960

Restaurant: Frank Pepe Pizzeria Napoletana

New Haven, Connecticut

How it happened: In New Haven, it ain’t pizza, it’s “apizza,” and you can credit the signature style of tomato pie (and purposeful misspelling) to Frank Pepe himself. The Italian immigrant opened his coal-oven pizza restaurant in 1925, giving his thin pies a signature char on the outside and a pleasant chewiness on the inside that New Haven’s now known for. Although the history of the now-iconic clam-topped white pie that was added to the menu in the 1960s is hazy, we do know this much: Pepe started putting chopped littleneck clams on the crust, pairing them with little more than garlic, grated cheese, oregano, and a slick of olive oil, and a hit was born. “The littleneck clams mingles nicely with the garlic and herbs, but it wouldn’t work out with the mozzarella so many pizza places utilize. Instead, the pecorino romano lets the clams take the starring role, and you have one of the -- if not the -- best pizzas in America...” gushed Men’s Journal.

Why it’s important: New Haven, and its singularly New England clam pie, has officially been on the pizza map for nearly a century. Not only that, but the pie has taken on new life at modern spots like the now-shuttered Franny’s in Brooklyn, Manhattan’s Pasquale Jones, and Pizzeria Delfina in San Francisco. Most importantly, it helped solidify seafood's place as a viable topping option. --Karen Palmer

Photo: Cole Saladino/Thrillist

24. Fried Calamari

Year: 1960

Restaurant: Randazzo's Clam Bar

Brooklyn, New York

How it happened: In the 1900s, the Randazzo family owned a seafood shop in Brooklyn’s Sheepshead Bay, which at the time was a fishing center. There, in 1960, Helen Randazzo added a small restaurant and bar, serving simple preparations of fresh fish smothered in her now-famous “Sauce” of long-cooked tomatoes with olive oil and oregano. Among the makeshift bar’s most popular dishes was lightly breaded and crisply fried calamari. Served with heaps of a spiced-up Sauce, customers deemed it the perfect accompaniment to a cold beer. “A bar gives you pretzels, potato chips, and peanuts, right? We gave calamari with hot Sauce,” said Paul Randazzo, a fifth-generation owner and Helen’s oldest surviving grandson. “The Sauce makes them drink more, you follow me? My grandmother was a genius!”

Why it’s important: When Randazzo’s started serving calamari -- or as anyone working at the restaurant will pronounce the dish, “gahlma” -- squid was used to bait fishing hooks, not to feed people. In the ‘60s, the catch fetched about 2 cents a pound, which is why the clam bar was able to serve it as a complimentary snack. Inspired by Helen Randazzo’s ingenuity, other fishermen’s bars in the area began to serve the dish. These days, it’s found on the menus of all kinds of restaurants, who still reap a healthy profit from a seafood whose current price hovers at around $6 per pound. -- LR

Photo: Randazzo's Clam Bar

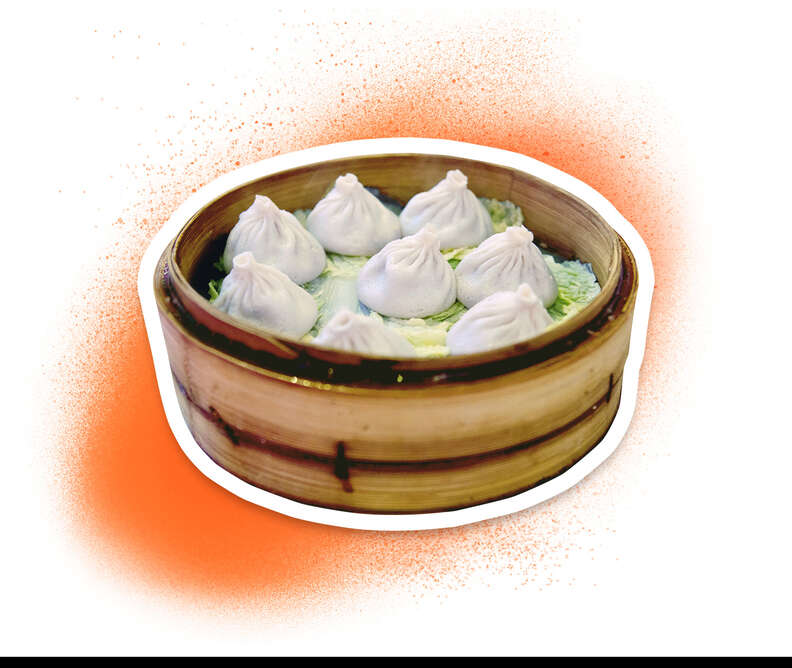

25. Peking Duck

Year: 1961

Restaurant: The Mandarin

San Francisco, California

How it happened: Until Cecilia Chiang opened The Mandarin in 1961, non-Chinese Americans didn’t know much about Chinese food outside of the Cantonese-ish stuff that had been tailored to their palates. (Think: chop suey.) But Chiang, an emigré who was raised in a 52-room mansion in Beijing, decided to invoke the flavors of northern China, and it forever changed Western perceptions of what Chinese food was and could be. “I didn’t know what Americans like or don’t like,” Chiang told PBS in 2015. “I just remembered what I had before in my life and put everything on the menu.” It’s thanks to her that pot stickers, hot and sour soup, and Peking duck entered the American-Chinese food vernacular. The duck, with its shatteringly crispy skin and bevy of accoutrements, soon became a best seller at the restaurant, which doubled as a social club for well-heeled San Franciscans and celebrities.

Why it's important: In the United States, where Chinese menus often serve a grab bag of dishes from disparate provinces (along with speciously un-Chinese appetizers like crab rangoon), Peking duck stands out because it is, by and large, faithful to the birds you might find within the great duck houses of Beijing. It was Chiang’s incredibly fortuitous stumble into cooking, and having little idea what her customers already liked, that led her to fall back on tradition -- and that’s exactly why we can now enjoy Peking duck as it should be served in untold restaurants around the US. -- MZ

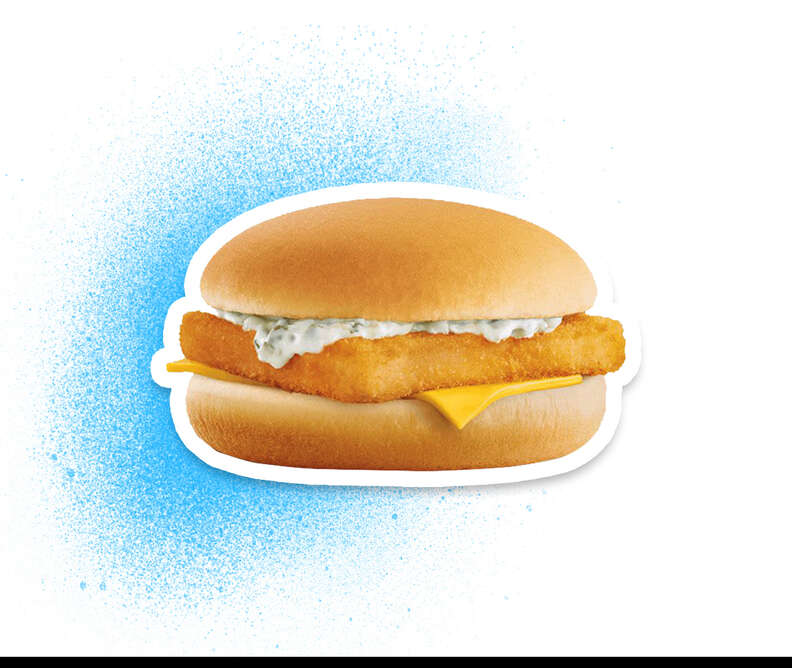

26. Filet-O-Fish

Year: 1962

Restaurant: McDonald's

Cincinnati, Ohio

How it happened: McDonald's franchise owner Lou Groen realized his Cincinnati-area restaurant was suffering a plummeting, potentially devastating drop in sales during the 40-day period of Lent, as much of the Catholic-heavy population of southwest Ohio would abstain from meat on Fridays -- or even altogether -- per Vatican tradition during the season of repentance. "On Fridays we only took in about $75 a day," Groen, who passed away in May of 2011, told The Cincinnati Enquirer in 2007. "All our customers were going to Frisch's [the local fried fish joint]. So I invented my fish sandwich, developed a special batter, made the tartar sauce and took it to headquarters." McDonald's head honcho Ray Kroc begrudgingly allowed the fish sandwich to grace Groen's menu alongside his own new vegetarian creation, the Hula Burger (a clearly misguided pineapple and cheese sandwich). He told Groen whichever dish sold more over Lent would earn a permanent spot on the national menu. And, well, have you ever heard of a Hula Burger?

Why it's important: Not only did the success of Groen's Filet-O-Fish single-handedly create the concept of nationally available fast seafood, it ushered in a new era of experimentation and menu expansion for the Golden Arches, and by extension, all of fast food. "My fish sandwich was the first addition ever to McDonald's original menu," Groen said. "It saved my franchise." The floodgates were now open. It made chain restaurateurs realize the value of menu diversity, and reading customer needs -- and it laid the template for the next half-century of fast-food innovation. -- WF

Photo: Courtesy of McDonald's

27. Hibachi Shrimp

Year: 1964

Restaurant: Benihana

New York, New York

How it happened: It's difficult to talk about Benihana and its influence in terms of one specific dish, since the entire experience of dining there is every bit as much about showmanship as it is about the food. When iconoclastic Olympic-wrestler-turned-ice-cream-truck-operator-turned-restaurateur Rocky Aoki opened the first Benihana in 1964, the huge steel teppanyaki grills served as stages where chefs would perform intricate theatrics with familiar ingredients that wouldn't challenge American palates still relatively unfamiliar with Japanese food: steak, chicken, and yes, shrimp, whose tails are removed, so that they can be artfully tossed with a spatula into the chef's hat and front pocket. Luckily the rest of the shrimp that's left behind happens to pair wonderfully with the onion volcano-fueled fried rice hearts.

Why it's important: After a glowing New York Times review turned it into an overnight sensation, Benihana was on its way to firmly embedding itself in the cultural lexicon, getting name-checked by rappers and showing up everywhere from The 40-Year-Old Virgin to Tyrese's house. The cultural heft is a bit surprising given Benihana's relatively modest footprint (66 locations) by chain restaurant standards. It could have something to do with the dozens of imitators that have popped up around the country that have channeled its format, shrimp tricks and all. "People say to me we've been to your Benihana in St. Louis, and we don't have a Benihana in St. Louis," said Jeannie Means, vice president of marketing. "And they're adamant about it because it's so similar." However, we all know there's only one true temple to hibachi shrimp. -- ML

Photo: Cole Saladino/Thrillist

28. Buffalo Wings

Year: 1964

Restaurant: Anchor Bar

Buffalo, New York

How it happened: On a cold, snowy night in 1964, Dominic Bellissimo was tending bar at his mom and pop’s red-sauce Italian joint. A group of his friends came in looking for a snack, and Bellissimo asked his mother Teressa to whip something up. Surveying the mostly empty walk-in, she spied a bunch of chicken wings she had been planning to use in a soup and was moved to throw them in the deep fryer. After tossing them with an improvised sauce of Frank’s Red Hot smoothed with butter, she served them to the hungry men alongside a plate of celery sticks and blue cheese dressing to tame the heat. “They dove right in,” said the Buffalo restaurant’s vice president Mark Dempsey. “The big, juicy wings were an instant hit, and the rest is history, so to speak.”

Why it’s important: Once the cheapest cut of chicken you could buy and relegated to stocks and soups, chicken wings steadily rose in popularity -- and price -- after Buffalo wings became the star of Anchor Bar’s menu, and were widely replicated in bars and restaurants throughout the country. Today, you can find the deep-fried wings served with everything from extra hot “Suicidal” sauces to glazes made from honey and soy. Plus, the concept of “Buffalo”-flavored everything has really taken off from pizza to sandwiches. -- LR

29. Poutine

Year: 1964

Restaurant: Le Roy Jucep

Drummondville, Quebec

How it happened: Some say poutine -- the Quebecois dish of French fries, cheese curds, and gravy -- originated in Warwick, Quebec, at Le Lutin Qui Rit in 1957, when a customer asked owner Fernand Lachance to mix fries and cheese curds in the same paper bag. "The identity of the inventor is the subject of some dispute, although a restaurant proprietor named Fernand Lachance is what detectives would call ‘a person of interest’ -- and for many years the humor about it within Canada could have been seen as a way of making a mildly deprecating jape about its home province," wrote Calvin Trillin in The New Yorker. Others claim that honor goes to Le Roy Jucep in Drummondville in 1964, when owner Jean-Paul Roy noticed guests ordering sides of cheese curds to accompany the diner’s fries and gravy. “Cheese, potatoes, and sauce” was too cumbersome for waitstaff to write, according to Le Roy Jucep, so it was shortened to “pudding,” resembling “putin.” Whichever tale is true, Le Roy Jucep had the foresight to trademark the dish in 1998. Today, it serves more than 20 tricked-out versions.

Why it’s important: Although it was born in Quebec, the comfort food has become one of Canada’s most recognizable culinary exports. Not only can it be found in dives and fancy restaurants alike across the provinces, the dish inspires cooks in the US, too. Americans can’t resist this booze-soaking mess of fries, gravy, and cheese, and chefs can’t resist toying with it, creating hoity-toity versions topped with the likes of foie gras and duck confit. -- AA

30. Key Lime Pie

Year: 1968

Restaurant: Joe's Stone Crab

Miami, Florida

How it happened: "It was born out of necessity," said Steve Sawitz, fourth-generation owner of Joe's Stone Crab, of his mother's famous Key lime pie. A reporter from Chicago had written about the delightful slice of Key lime pie he ate at Joe's in 1968, even then an iconic Miami restaurant known for, what else, its stone crab. The only problem was that Joe's didn't have a Key lime pie on its menu. Instead of balking at the mix-up, Jo Ann Sawitz, Steve's mother, embraced this as "not just an opportunity, but an obligation," as he put it. Already an adept baker, Jo Ann configured the recipe that's still being used today: butter and graham cracker for the crust, sweetened condensed milk, egg yolks, and freshly squeezed key lime juice for the filling, though the limes -- not always real Key limes as the indigenous crop was wiped out from the Great Miami Hurricane that pummeled the Keys in 1926 -- are no longer cut and squeezed by hand.

Why it's important: Only four states have an official state pie, each a pillar of traditional crusted American desserts: apple (Vermont), pumpkin (Illinois), pecan (Texas), and Key lime (Florida). And the ones they make at Joe's continue to be in such demand that there's a dedicated room where a dedicated baker churns out the tart custard pies. "It's become the most popular thing on the menu. By far," Sawitz said. Granted, Joe's didn't invent this classic American dessert, but they quite possibly perfected it, and certainly popularized it. -- LB

31. Animal Style Fries

Year: c. 1969

Restaurant: In-N-Out Burger

Baldwin Park, California

How it happened: The origins of In-N-Out Burger's legendary "Animal Style" fries is a SoCal secret shrouded in more mystery than the next Star Wars script. And even the woman who literally wrote the book on In-N-Out can't be fully sure how exactly it came to fruition. But legend posits that the clean-cut chefs who ran the flagship In-N-Out location in Baldwin Park, California in the '60s had an intense disdain for the rowdy surfers who would frequent the location, often referring to them as "Animals." When they needed shorthand for the customized special sauce these scruffy teens liked to put on their fries and burgers (basically, Thousand Island dressing with cheese, and grilled onions), they naturally just called it "Animal Style." Regardless of the origins, it remains the flagship item on In-n-Out's secret (but not-so-secret, anymore) menu.

Why it's important: "Secret menus" have long been fodder for blogs, fan groups, and food journalism deep-dives (this website being no exception) -- and all the clandestine ordering started here. In-N-Out has only added to its cult-like status as one of the most beloved fast-food restaurants in the world by not only accommodating guests who want to play mad scientist with their menus, but fully embracing the movement. If you've ever felt the thrill of ordering a McGangBang, or even reading about it, you have In-N-Out and their ubiquitous "Animals" to thank. -- WF

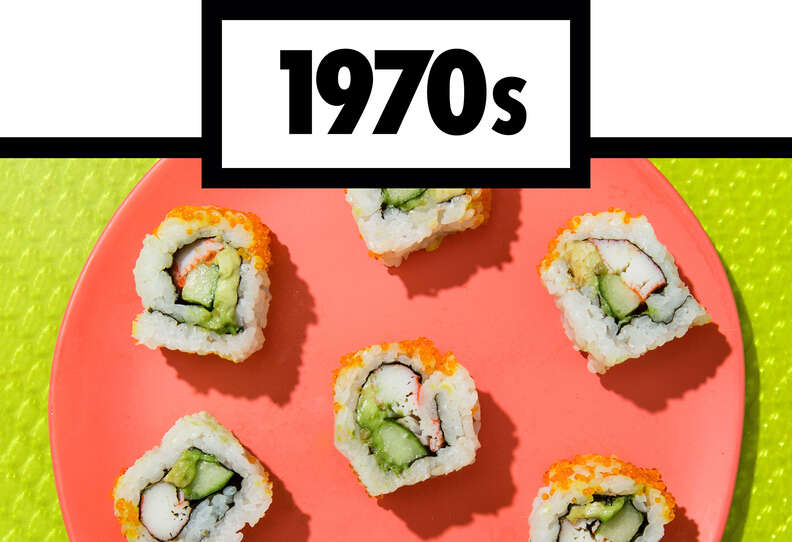

32. California Roll

Year: c. 1970

Restaurant: Tokyo Kaikan

Los Angeles, California

How it happened: The California roll needs no introduction, yet its history is far from clear. The invention of this ubiquitous roll has been claimed by many over the years. First is Tokyo Kaikan, one of LA’s first sushi restaurants, where a chef named Ichiro Mashita allegedly opted to replace the expensive and difficult-to-source fatty toro with creamy avocado, plentiful as they are in California. International Marine Products Inc, which owned the now-shuttered Tokyo Kaikan, still claims to be “the birthplace of the now famous California roll.” Another contender, however, is Hidekazu Tojo, a Japanese sushi chef who emigrated to Canada in the 1970s, and who claims that he invented the roll, originally called “Tojo-maki,” because Westerners were put off the flavors of raw fish and seaweed, which he replaced with cooked crab and avocado. “A lot of people from out of town came to my restaurant -- lots from Los Angeles -- and they loved it. That's how it got called the California roll,” he told the Globe and Mail in 2012.

Why it's important: Regardless of who invented it or how closely it resembles traditional Japanese maki, the California roll has long served as the gateway drug to a broader appreciation of sushi for many Westerners -- and sushi restaurants have boomed as a result. Not only that, but the highly palatable roll might well be responsible for the rise of grocery store sushi, which comprised a $705 million market in the US in 2015, perForbes. That’s one hell of a lot of avocados. -- MZ

Photo: Cole Saladino/Thrillist

33. General Tso's Chicken

Year: c. 1970

Restaurant: Uncle Tai's Hunan Yuan and Hunan

New York, New York

How it happened: Sugar-shellacked and a shade of otherworldly red, General Tso’s chicken has remained a staple of American Chinese menus for decades. The original version, however, barely resembles its Western cousin. It was devised by Peng Chang-kuei, who served as the official banquet chef for the Chinese government after World War II, before emigrating to Taiwan where he created the sour, salty, and spicy dish he would name after a 19th-century Hunanese military hero. In the early 1970s, David Keh, who owned Uncle Tai’s Hunan Yuan, and chef TT Wang, who owned Shun Lee Dynasty and Shun Lee Palace, and who cooked at Hunan Restaurant, independently traveled to Taiwan and decided to put Peng’s chicken dish on the menus of their competing restaurants back in New York City -- but with a jolt of sugar added. “They both felt, as many Chinese chefs who are feeding Caucasian people around the world do, the need to emphasize the sweet side of the food for non-Chinese people,” said restaurateur Ed Schoenfeld, who worked at Uncle Tai’s in the 1970s. Ultimately, however, Schoenfeld says that it was TT Wang’s blueprint for the dish that became popular the world over.

Why it's important: By some estimates, General Tso’s chicken is the most popular Chinese dish in America, even if Peng, who died in 2016, would hardly recognize it. “Chef Peng was baffled by the broccoli in all the photos of General Tso’s chicken from America,” said Jennifer 8 Lee, who co-produced the 2014 documentary The Search for General Tso. As Lee wrote in The Fortune Cookie Chronicles, the dish is as American as apple pie: “You can now eat the general’s chicken in all-you-can-eat $4.95 supper buffets along interstate highways, at urban takeouts with bulletproof windows, and in white-tablecloth establishments that have received starred reviews in The New York Times.” -- Matthew Zuras

34. Chicken Tikka Masala

Year: 1971

Restaurant: Shish Mahal

Glasgow, Scotland

How it happened: On a cold and rainy night in Glasgow, Ali Ahmed Aslam was working in the kitchen of his restaurant and was dealing with a stomach ulcer that made it hard to eat anything but Campbell’s tomato soup. A customer in the dining room sent back an order of chicken tikka, a marinated grilled chicken dish, complaining that it was too dry. “Aslam took it back inside and he mixed into the curry something called Campbell’s condensed tomato soup, and from that, the chicken tikka masala was invented,” says Andleeb Ahmed, director of Shish Mahal. The customer loved it, and it quickly spread throughout the UK and became one of the regions most popular dishes.

Why it's important: Chicken tikka masala is the result of tradition and on the spot ingenuity, using what was available to adapt a traditional dish. Some say that the dish actually originated in the Punjab region of India a long time before the Shish Mahal story, but the controversy of the origins of the dish pales in comparison to the love that the United Kingdom has for the dish. In 2001, while giving a speech about the benefits of multiculturalism, Robin Cook, foreign secretary representing Great Britain, declared chicken tikka masala as the national dish of England and “a perfect illustration of the way Britain absorbs and adapts external influences.” Since its inception in the 1970s, it’s become one of the most ubiquitous dishes on Indian restaurant menus around the world. -- KW

35. Crispy Orange Beef

Year: 1971

Restaurant: Uncle Tai's Hunan Yuan

New York, New York

How it happened: Like General Tso’s chicken, crispy orange beef is a chopped-and-screwed import. “We introduced crispy orange beef to America and it was a riff on a cold appetizer,” said Ed Schoenfeld, who worked for restaurateur David Keh at Uncle Tai’s in the 1970s and claims that the original dish hailed from the Sichuan banquet food tradition. He said that Chef Tai took “cold orange beef, which is made with aged, dry tangerine peel, ginger, and scorched chilies and scallions” and coupled it with a new technique for frying tenderized beef until it was shatteringly crispy and melt-in-the-mouth, transforming a typically cold dish into a hot one. “His version of that is pretty much what’s become popular except, as with General Tso’s chicken, more often than not it’s degraded,” Schoenfeld added.

Why it's important: A staple of American Chinese menus everywhere, crispy orange beef represents not merely a corruption of classical Chinese cooking, but an inventive spirit and a desire to fuse tradition with new technique -- at least in the dish’s original form. Schoenfeld might be right about the degradation of crispy orange beef; Mimi Sheraton’s 1981 review of Uncle Tai’s competitor Shun Lee West dismissed that restaurant’s iteration as “leathery and afloat in orange grease.” Many dime-a-dozen Chinese restaurants fare no better, but there are still plenty of temples to the golden age of Chinese cooking in America (Schoenfeld’s RedFarm, for example) keeping the crispy beef flame alight. -- MZ

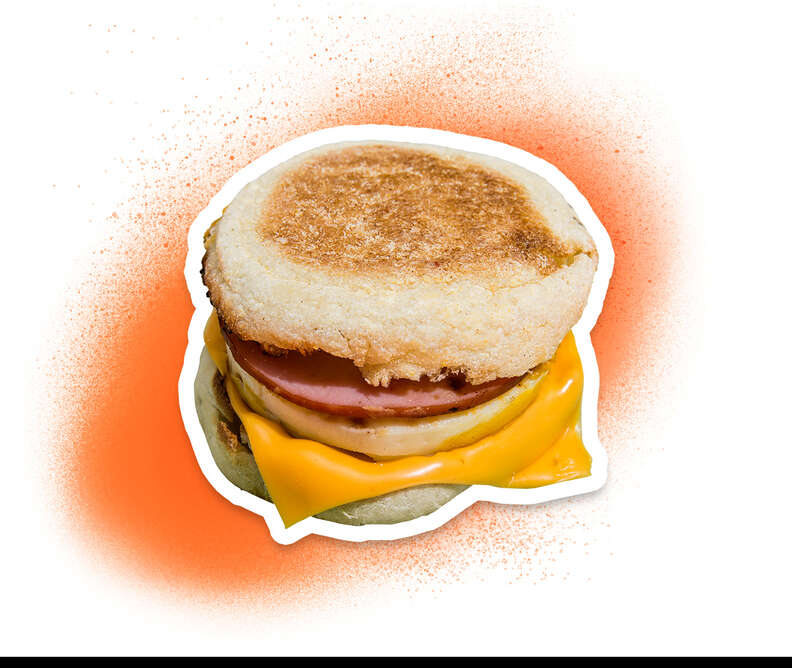

36. Egg McMuffin

Year: 1972

Restaurant: McDonald's

Santa Barbara, California

How it happened: It might seem borderline ludicrous now, as the Egg McMuffin is as synonymous with American mornings as the Today show, but the inventor of the fast-food breakfast icon was initially scared to show his boss his new idea. Herb Peterson, the operator of a McDonald's in Santa Barbara, refused to tell McDonald's founder Ray Kroc any details about his breakfast sandwich, and insisted he show it to him, firsthand. "He didn’t want me to reject it out of hand, which I might have done, because it was a crazy idea," Kroc stated in his autobiography. "I boggled a bit at the presentation. But then I tasted it, and I was sold." Peterson based the idea around a handheld, stripped-down version of eggs Benedict -- complete with cheese, Canadian bacon, and a griddle-fried egg -- and it helped solve a problem Kroc and company had grappled with for years: getting people in the door for food before noon.

Why it's important: If you've ever hit up a fast-food restaurant before 11:30am -- you have the Egg McMuffin to thank. Not only did it popularize the fast and easy on-the-go breakfast, it introduced the entire country to the concept of a breakfast sandwich. "McDonald's came out with the McMuffin in the early '70s, and it became a known and available commodity all over the country," said food historian and sandwich expert Joel Jensen. "Now, everyone in the country could drive a couple miles and get a breakfast sandwich. It was introduced into the cultural consciousness." The Egg McMuffin turned Micky D's into a breakfast joint, invented the concept of fast-food breakfast, and let millions of customers all over the world grab a few extra minutes of sleep -- as breakfast was now just a drive-thru stop away. -- WF

Photo: Cole Saladino/Thrillist

37. Loaded Potato Skins

Year: 1974

Restaurant: TGI Fridays

Dallas, Texas

How it happened: Other restaurants (most notably R.J. Grunts of the Chicago-based Lettuce Entertain You empire) have competing claims surrounding the creation of the potato skin, but the version that ultimately conquered America's hearts and your grocer's freezer traces its lineage to Fridays, back in its heyday as a swinging '70s singles bar. A chef in the midst of a batch of mashed potatoes decided to toss some skins in the fryer, and after some Cheddar cheese and bacon joined the party, a bar food sensation was born. "It was mind-bogglingly successful," said Walt Henrion, one of the partners who convinced founder Alan Stillman to extend his NYC bar to franchises around the country, starting in Dallas. "We started selling them at $1.65 for a little basket of six halves. In one month we went from $1.65 to $4.25 because we couldn't produce for the demand."

Why it's important: According to Henrion, it took longer than it should have for other competing chains to notice how many potato skins Fridays was slinging, but a few years later, copycat versions were appearing everywhere, and before long it was an appetizer staple on par with Buffalo wings and nachos. Beyond that, today's menus feature all manner of "loaded" potato items for which everyone understands without so much as a glance at the description that "loaded" will entail melted cheese and crispy bits of bacon. That said, no permutation of potato perfectly harnesses a concentrated payload of toppings quite the way a well-hollowed potato skin does. -- ML

Photo: Cole Saladino/Thrillist

38. Breakfast Burrito

Year: 1975

Restaurant: Tia Sophia's

Santa Fe, New Mexico

How it happened: Though this Southwestern café, opened in 1975 by Jim and Ann Maryol, can’t lay claim to inventing the breakfast burrito, it’s Jim who gave the tortilla-wrapped meal its name. “New Mexicans have forever been putting eggs, ham, potatoes, sausage, and cheese inside a tortilla, and eating it for breakfast,” said his son Nick, who took over the business in 2004. “My father is merely the first person to call it a ‘breakfast burrito.’” The overstuffed flour tortilla, Tia Sophia’s most popular dish, also comes with a crowning of New Mexican most prized ingredient: chilies. Simply prepared using either red poblano peppers or unripe green ones, plus salt and garlic, the exemplary toppers have been known to inspire indecision in diners. In the 1970s, Nick recalled, waitress Martha Rutino grew tired of all the “hemming and hawing” and told customers to “just get the Christmas”: a burrito striped with both red and green varieties.

Why it’s important: You can now find some version of a breakfast burrito all over the country, from small local burrito shops to fast-food joints (ahem, Taco Bell). Call it Tex-Mex or call it Southwestern, it’s the regional flavor, incorporating local ingenuity and New Mexican ingredients, that set Tia Sophia’s apart. “I knew we had reached cultural critical mass when I saw Walter White on Breaking Bad preparing his wife chicken enchiladas, Christmas-style,” said Nick. -- LR

39. Chicken and Waffles

Year: 1975

Restaurant: Roscoe's House of Chicken and Waffles

Los Angeles, California

How it happened: Toward the tail end of the Harlem Renaissance in 1938, restaurateur Joseph T. Wells opened Wells Supper Club on Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard, and quickly attracted the jazz musicians (and hangers-on) finishing up gigs at nearby clubs. Arriving too late for dinner but too early for breakfast, the guests were offered a hybrid of both: a fluffy waffle piled with crisp pieces of fried chicken. The mash-up dish became a trend in Harlem, where Roscoe’s founder Herb Hudson was living at the time. But when he decamped to Los Angeles in 1975, there were no chicken and waffles to be found. “I decided to make my own,” Hudson recalled. The idea took off, quickly inspired copycat renditions around town. In addition to the inherent appeal of the dish, Angelenos were attracted by its Harlem origins. “There really weren't any minority or black-owned businesses in Hollywood at the time, so people were responsive and excited for something new,” Hudson said.

Why it’s important: While chicken and waffles consecrates the holy union of sweet and savory, and is basically a precursor the phenomenon that would become brunch, its cultural relevance stretches even further than that. By bringing this African-American innovation to Los Angeles and making it a sensation, Hudson scored a triumph for the black restaurant community. Now everyone is clamoring to eat chicken and waffles. -- LR

Photo: Dustin Downing/Thrillist

40. Pasta Primavera

Year: 1977

Restaurant: Le Cirque

New York, New York

How it happened: While it sounds like it was created in a nonna’s kitchen in the hills of rural Tuscany, pasta primavera was actually born during a trip to Nova Scotia with a group that included New York Times food critic Craig Claiborne, and Le Cirque owner Sirio Maccioni and his wife Egi, who were in charge of cooking a Sunday lunch. “My father said, ‘Let's just do our family tradition,’ which is pizza and pasta on Sunday,’” Sirio’s son Marco Maccioni recalled. “My mom woke up to make the pizza. My father, slept a little bit more. My mom used tomatoes for her pizza sauce. And when my father woke up, he found there were no more tomatoes. He was planning on serving handmade spaghetti with fresh tomatoes and olive oil. He said, ‘How am I going to make spaghetti with fresh tomatoes if you used all the tomatoes?' My mom said, ‘You should have woken up.’” Sirio used what he could find: frozen broccoli, peas and asparagus, fresh zucchini and mushrooms… and two measly tomatoes. He tossed them in a pan with cream, basil, garlic, and pine nuts, shaved on some Parmesan, and served it over the spaghetti. “Craig Claiborne asked, ‘What is this fabulous pasta?’ My father answered, 'It's primavera,’ because it was springtime,” Marco said.

Why it’s important: Back in New York, Craig Claiborne asked the Maccionis to cook the same pasta at his home in Amagansett. They did, and Claiborne published the recipe in The New York Times in October 1977. Immediately, the dish became Le Cirque’s signature, though it has never actually appeared on the menu. The tableside service of the pasta caused so much buzz that diners didn’t have to see it on the menu to order it. It became perhaps the longest-running “off-the-menu” item in restaurant history, not to mention the go-to vegetarian entree option at hotel restaurants around the country. -- Kathleen Squires

Photo: Cole Saladino; Styling: Perry Santanachote

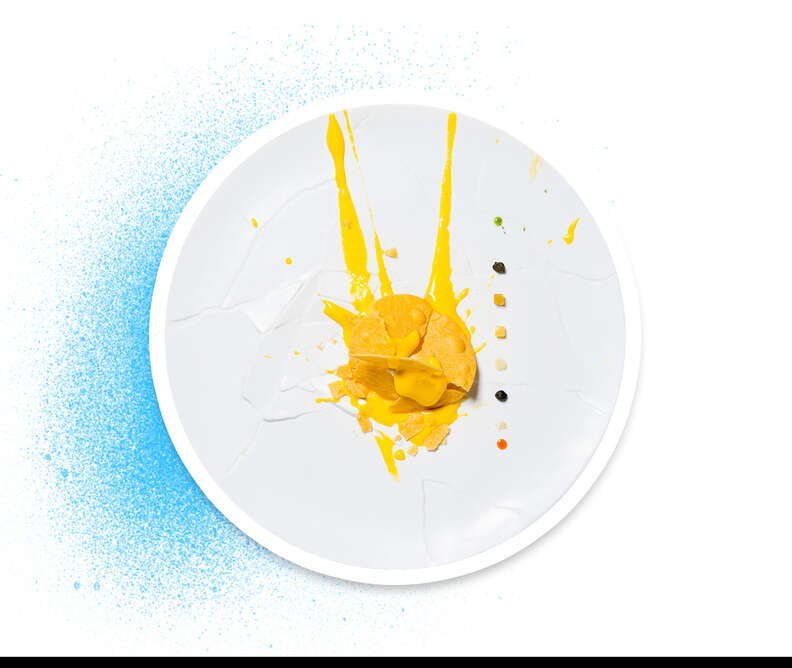

41. Gargouillou

Year: 1980

Restaurant: Lou Mazuc

Laguiole, France

How it happened: Reared in the rambling French countryside, Michel Bras was always drawn to nature. Before opening his eponymous restaurant in 1992, the self-taught chef helmed Lou Mazuc, his parents’ hotel-restaurant. It was during this time, inspired by a walk through pastures in bloom, that he dreamed up his refined rendition of an old Auvergne stew with potatoes called gargouillou: a stunning assemblage of some ever-changing 60 vegetables, herbs, and flowers like fern, amaranth, nasturtium, and Alpine fennel along with a grounding base of cured ham. This composition of myriad shapes and textures is arguably the world’s most remarkable salad. "For me, his gargouillou is an incredible display of technique and a clear example of a chef's true understanding of vegetable cookery,” wrote New York chef Wylie Dufresne in an essay for Saveur about cooking for Bras, his idol.

Why it’s important: Bras championed the vegetable with sincerity and elegance well before other chefs, leading them to consider the merits of their own backyards. The delicate, vibrant gargouillou has since spawned a number of Stateside versions from chefs like David Kinch (Into the Garden at Manresa in Los Gatos, California) and Daniel Patterson (Abstraction of Garden in Early Winter at San Francisco's Coi). “Michel Bras is one of the most imitated chefs in the world, and with good reason," Dufresne added. -- AA

Photo: Cole Saladino; Styling: Ali Nardi

42. Pommes Puree

Year: c. 1980

Restaurant: L'Atelier de Joël Robuchon

Paris, France

How it happened: Mashed potatoes have always been a comfort food, a rustic and filling side dish made from creaming the humble spud with some cream and perhaps a knob of butter. That was until star French chef Joel Robuchon got his hands on them. The chef said that he is obsessed with elevating the most basic dishes into something magical, and he wanted to do it with mashed potatoes in particular, because people just really love potatoes. His version is just four ingredients, but it is far from simple to make. There is a full pound of butter for every two pounds of potatoes that is beaten in one tablespoon at a time, and then passed through a sieve multiple times. The result is ethereally creamy potatoes that has become one the biggest stars of fine dining.

Why it's important: Robuchon showed the world that it is possible to transform any dish, even the most humble one made of mashed potatoes, into an incredibly luxurious experience. His pommes puree are so popular that he has them on the menu at every one of his 14 restaurants in over 10 countries across the globe. It is one of the first dishes that many hopeful chefs learn how to make and it helped confirm the notion that there is no such thing as too much butter. -- K. Shah

Photo: Cole Saladino / Thrillist

43. Chocolate Lava Cake

Year: 1981

Restaurant: Bras

Laguiole, France

How it happened: The '80s: a time for big hair, synth music, and chocolate cake with runny centers and messy origin stories. In 1981, Michel Bras debuted his chocolate coulant, which involves submerging a sphere of ganache in a ramekin of chocolate cake batter, at his namesake restaurant in Laguiole, France, following a trip he took with his children. "I wanted to translate the emotion evoked by coming home to find a mug of hot chocolate after a day of skiing," he explained. Six years later, a young Jean-Georges Vongerichten created his version on accident, when he served 500 underbaked chocolate soufflés, made from his mother's recipe, at the now-shuttered Lafayette inside New York City's Drake Hotel. "I couldn't believe I had just served raw cake!" he recounted. Vongerichten received a standing ovation from the guests, and the chocolate Valrhona cake was added to the permanent menu the next day.

Why it's important: Regardless of who invented it, the chocolate lava cake quickly became the pinnacle of fine dining, with chefs across the country clamoring to add a version to their dessert menus. From there it was a quick expansion to Disney World in 1997, and just one year later, the lava cake became one of the country's most recognizable treats, making appearances everywhere from chain restaurants to the freezer aisle of Walmart. It has become so ubiquitous that food writer Mark Bittman eventually ordained it the "the Big Mac of desserts." -- KS

Photo: Cole Saladino/Thrillist

44. Goat Cheese Salad

Year: 1981

Restaurant: Chez Panisse

Berkeley, California

How it happened: In American cheese circles, one of the most important meet-cutes of the 20th century just might be between Alice Waters, proprietor of the beyond-influential Chez Panisse in Berkeley, and Laura Chenel, a cheesemaker in Sonoma County. Legend has it that Waters was so impressed by Chenel’s goat cheese during an early 1980s tasting that she placed a standing order for the restaurant -- thus creating one of her most iconic dishes, a humble combination of breadcrumb & thyme-coated goat cheese baked and served with greens and garlic toast. "Goat cheese was not really available in those days, or at least not goat cheese made in America,” said Waters. “Laura Chenel was one of the first ones who made it commercially available, and I loved it." Waters noted in 1999’s Chez Panisse Cafe Cookbook that the dish is one of two they’ve had on the Cafe’s menu since day one. As for its origins, “I can't remember exactly where the recipe for the salad came from, but my mind was in the South of France,” said Waters.

Why it’s important: In a 1983 article in the New York Times about the growing popularity of goat cheese that included a recipe for the salad, then-food editor Craig Claiborne noted, “Alice Waters, the owner-chef of Chez Panisse in California, was one of the first to experiment with baked goat cheese in this country. As a result, she has become justly well known for her baked goat cheese with garden salad...” Aside from Waters’ countless other contributions to the food world, one could also say she’s responsible for the ubiquity of goat cheese salads on menus around the country. -- KP

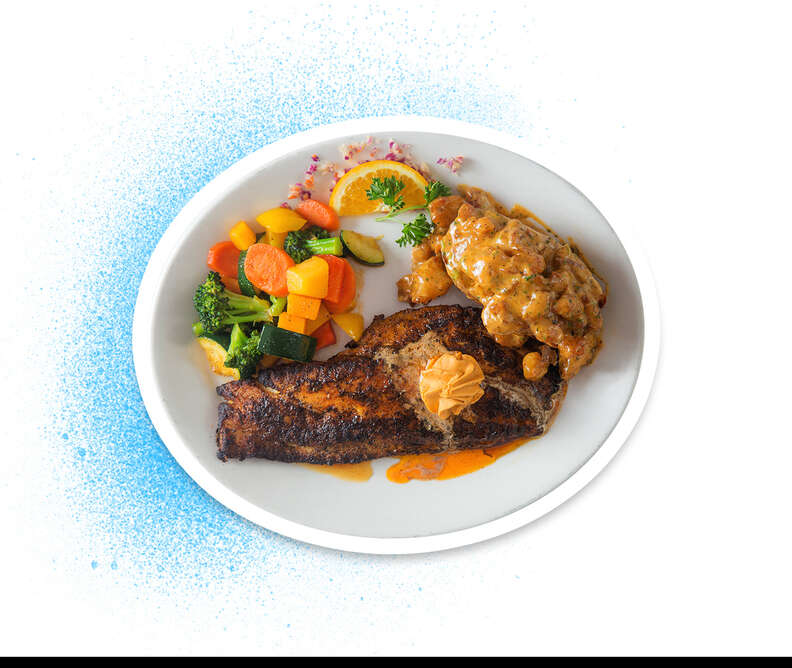

45. Blackened Redfish

Year: 1982

Restaurant: K-Paul's Louisiana Kitchen

New Orleans, Louisiana

How it happened: Though K-Paul founder and chef Paul Prudhomme passed away in 2015, his restaurant, and spin on Cajun cuisine live on. Current executive chef Paul Miller said that Prudhomme’s famous blackened redfish was concocted when Prudhomme was still chef at Commander’s Palace, in the late '70s and early '80s: “I was working with him at Commander’s, and we were experimenting with using a huge, cast-iron pot. We loved how the pot was giving everything a grilled and charcoal-pit taste. But it was chef Prudhomme’s seasoning blend that took it to a new level. That seasoning, with a hit of clarified butter in a very hot skillet, brings out the moisture of the fish, and gives it a dark, sweet color. The mixture of juices from the fish and the seasoning -- paprika, salt, onion powder, garlic powder, cayenne pepper, thyme, oregano -- and the butter and the cast-iron skillet is just… magic.”

Why it’s important: Prudhomme’s method started a whole Cajun cooking trend across America. The Times-Picayune even said that the recipe “nearly wiped the redfish off the Gulf fisheries map,” because of its popularity. The trend hit critical mass on a national scale, and now “blackened” is simply another cooking method, like “roasted” or “fried.” -- K.Squires

Photo: C. Ross / Thrillist

46. Salmon Pizza

Year: 1982

Restaurant: Spago

Los Angeles, California

How it happened: In 1982, a 33-year-old chef named Wolfgang Puck opened a restaurant on the Sunset Strip in West Hollywood called Spago, serving what would soon be known as "spa cuisine" -- meaning French technique applied to California ingredients with the occasional nod to Asian cuisine. He was working in the kitchen one night when legendary actress Joan Collins ordered smoked salmon with buttery brioche bread. Puck panicked. He didn’t have any brioche left to make the actress’ order. Improvising, he topped a freshly baked pizza crust with creme fraiche, dill, smoked salmon, and a spoonful of caviar on each slice. The actress loved it. Word spread about the dish, and soon, celebrities filled the dining room to try Puck’s salmon pizza. Spago’s location may have changed from West Hollywood to Beverly Hills, but the smoked salmon pizza has been on the Spago menu since it opened.

Why it's important: If you like toppings on your pizza besides the standard pepperoni and vegetables, you have Puck to thank. The salmon pizza, which is the official dish of the Oscars, helped usher in a new era of stunt pizzas, where people started to become more adventurous with their pies. In particular, the salmon pizza served as the base for a new style of distinctly California pizza, which favored fresh ingredients over heavy cheese, sauce, and greasy toppings. -- KW

Photo: Cole Saladino; Styling: Ali Nardi

47. Bread Pudding Soufflé

Year: 1983

Restaurant: Commander's Palace

New Orleans, Louisiana

How it happened: It was the 100th anniversary of Commander’s Palace in 1983 that prompted the addition of the now-legendary bread pudding soufflé to the menu, said co-proprietor, Ti Martin. “We did an event called the American Cuisine Symposium. We invited people from all over the country -- Larry Forgione, Florence Fabricant, Jonathan Waxman, and everybody who was pushing the American food scene forward,” said Martin. “The discussion was centered around the question, ‘Is there an American cuisine?’ because we all still had this inferiority complex to Europe. At the time, Paul Prudhomme was the chef at Commander’s, and they were really pushing to lighten things.” The famously portly chef had the idea of “lightening” a rich soufflé involved using leftover French bread. Martin added that while Americans were familiar with traditional French Grand Mariner soufflé, “They might have been a little intimidated by it. But if you say ‘bread pudding soufflé,’ America can relate to that.” The result: a sweet, eggy dessert, dotted with raisins, generously garnished with whiskey cream sauce, characteristically New Orleans in its decadence.

Why it’s important: The mash-up dessert exemplifies the high-low essence of American cuisine. As the Southern Food and Beverage Museum declared, the dessert allowed bread pudding “to rise above its humble origins.” Today, it can be found on menus across the country of restaurants both high- and low-end. -- K. Squires

48. Roast Chicken With Potatoes

Year: 1984

Restaurant: Jams

New York, New York

How it happened: When 33-year-old chef Jonathan Waxman opened the rollicking, we-came-to-party restaurant Jams on Manhattan’s Upper East Side in 1984, he simply cooked like he always had at places like Berkeley’s legendary Chez Panisse and Michael’s in Santa Monica: using the best, seasonal ingredients prepared with minimal fussiness. New York City couldn’t get enough of his so-called “California cuisine.” His iconic chicken followed that mantra: an excellent product (a fatty, expensive bird sourced from upstate farmer Paul Kaiser) not overly messed with (nearly fully deboned and grilled skin-side down over charcoal to crisp the skin, then flipped quickly) and made delicious with a few accoutrements (a brown butter and tarragon sauce and French fries that, due to a minor obsession on Waxman’s part, took three days to prepare). “I wasn’t so much making this an intellectual pursuit -- just trying to make foods I’d had better,” he said.

Why it’s important: Waxman didn’t set out to reinvent the wheel -- but nevertheless, the self-proclaimed “misfit” who’d cooked in France, then came of age on the West Coast, helped to spread the gospel of California cuisine to the East Coast and to make chicken well, cool, again. He also jokes that he'll "probably have a chicken head on my gravestone when I die.” Considering that he’s since created another iconic bird at his West Village mainstay Barbuto, we’d have to agree. -- KP

49. Tableside Guacamole

Year: 1984

Restaurant: Rosa Mexicano

New York, New York

How it happened: Chips and guac are basically a must-do first step when sitting down at a Mexican restaurant, but there's something extra special about the increasing number of establishments that take the effort to prepare it tableside. You can thank Josefina Howard for that, the founder of Rosa Mexicano, a New York-based chain that now boasts locations across the country. “Tableside guacamole was something that was being done at home by Josefina Howard,” said Chris Sellati, Rosa Mexicano's regional executive chef. “The point of Latin hospitality is to invite people in as if they had stepped into our home, or, in this case, our kitchen.” Having a trained guacamole expert roll up to your table and gently fold hunks of avocado with bits of onion and sprigs of cilantro right in front of you makes it an occasion. “It’s dinner and a show,” said Sellai.

Why it’s important: Guacamole had graced the menus of America’s Mexican restaurants long before Rosa Mexicano made tableside guac a mainstay, but the increasingly popular ritual has given Mexican restaurants another avenue to elevate the dining experience and give customers a peek behind the curtain. The hunger-inducing satisfaction that comes with observing a pile of ripe avocado mashed into creamy guacamole undoubtedly played a role in creating the current avocado-obsessed world in which we find ourselves. -- Amy Schulman

Photo: Courtesy of Rosa Mexicano

50. Spam Musubi

Year: 1985

Restaurant: Joni-Hana

Kauai, Hawaii

How it happened: While its appeal continues to baffle some mainlanders, Spam has remained popular among Hawaiians ever since World War II, when the US military presence on the islands demanded a continuous supply of cheap protein to feed hungry soldiers. Four decades of “spiced ham” later, Barbara Funamura of Kauai’s Joni-Hana restaurant introduced the now-ubiquitous Spam musubi, a one-hand snack of rice, nori, and a slice of the grilled luncheon meat. Like its close cousin onigiri, the original Spam musubi was triangular in shape, until a Joni-Hana restaurant worker suggested using a rectangular mold to form the rice bricks. “It sold really well from Joni-Hana at the Kukui Grove Center,” Dan Funamura, Barbara’s husband, told a reporter in 2016. “There were the training people from Honolulu who were working with Foot Locker and the Sears store. They all came in and were laughing about it, but within a year, it was all over the state.”